For many Dutch, the Golden Coach is primarily the carriage that is used for the opening of the parliamentary year on the third Tuesday of September. The king and queen drive to the Ridderzaal at the Binnenhof, where the king reads the throne speech. Enthusiastic spectators along the route wave at the opulently decorated coach drawn by eight horses and accompanied by a procession of footmen and coachmen. Others may associate the Golden Coach with special royal occasions, such as weddings and inaugurations. These often take place in Amsterdam, sometimes accompanied by loud protests. In the last half century, the coach has been the target of smoke bombs, a paint bomb, and a tea light holder. In other words, the Golden Coach is more than simply a means of transport for the king or queen; it is symbolic of the royal family. For many, something to cheer; for others, something that raises the question of whether it is still appropriate in this day and age, or whether it should be opposed.

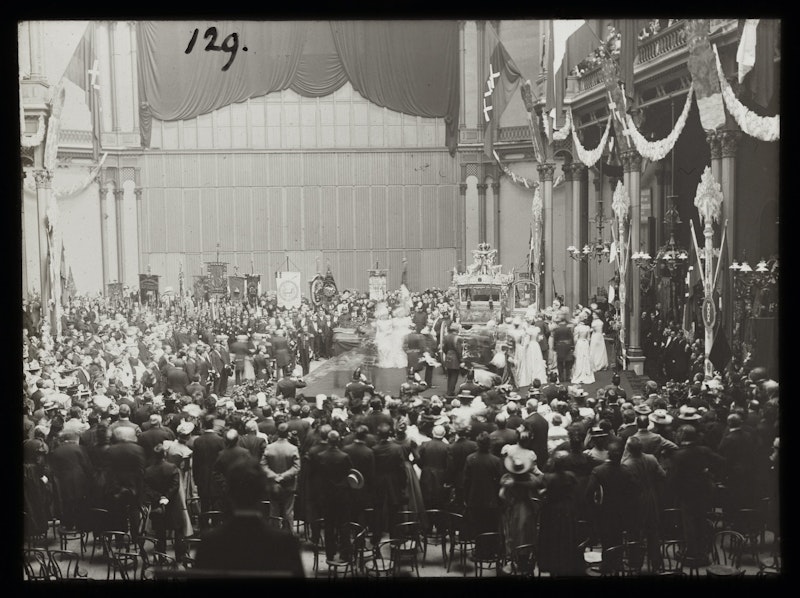

Presentation of the Golden Coach to Queen Wilhelmina in the Palace of Popular Diligence, September 7, 1898. Amsterdam City Archives.

Not many people know that the Golden Coach was a gift from the people of Amsterdam. It was given to the first female monarch of the Netherlands, Queen Wilhelmina, who celebrated her eighteenth birthday on August 31, 1898, and was inaugurated shortly thereafter in the capital. How and why this gift came about is worth an exhibition in its own right, not least because the coach was financed through a collection, the focus of which was in the Jordaan, one of the poorer areas of the city at that time. This corresponds to the popular modern phenomenon of crowdfunding, but also raises questions: why did these poor people in Amsterdam collect money for a luxurious gift for one of the richest families in the nation? What was the position of the monarchy in the Netherlands at that time? After all, this was a country which had, in the seventeenth century, just as resolutely advanced the model for the republic as a form of government.

In the past year the coach has been in the news a great deal because of one of the panels which decorates it. On this panel, entitled Tribute from the Colonies, the painter Nicolaas van der Waay depicted a seated white woman being presented with gifts by people of color, some of whom are kneeling. It is an allegory which expresses the relationship between the Netherlands and the colonial regions in the East (Indonesia), and West (Suriname and the former Dutch Antilles, including the islands of Curaçao and Aruba). The artist Ruben La Cruz, who originates from Curaçao, protested this representation at the Summer Carnival in Rotterdam as far back as 1990. And in 2009 it was the activist Jeffry Pondaag who demanded that the coach no longer be used; that it was high time for reparations to be paid to the victims of colonialism. In 2011 two members of parliament, Mariko Peters (GroenLinks) and Harry van Bommel (SP), put forward a motion to discontinue the use of the coach. The worldwide Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, and the associated backlash against depictions of colonial domination in the public space, accelerated opposition to the use of the coach because of the Tribute from the Colonies panel. A young generation of activists like De Helden van Nooit (The Heroes of Never) announced on social media that they would not stop defacing statues in the public space until the coach was no longer used. An online petition with the same goal, initiated by social geographer Nugah Schrestha, received almost 8,000 signatures.

AiRich, BLOODY GOLD. TRIBUTE FROM THE COLONIES / WHAT ABOUT REPAIRING THE DAMAGE? 2021. Collage. Courtesy of the artist and CBK Zuidoost.

The Golden Coach has not been seen for a few years now, because it has been under restoration since 2015. So can it be returned to use? Before deciding on its future, the Amsterdam Museum, the museum for the culture of the city of Amsterdam, was loaned the coach upon completion of the restoration. From June 2021 until February 2022, the museum organized an exhibition about this controversial gift, along with a full public program of education and research. In this way we can see and experience the many different significances of Golden Coach, both now and in the past. Our aim is to achieve a broad and multifaceted discussion about its present, past, and future.

Different views and connections

We live in an age when there are (structural) inequalities and conflicts in society in many areas. In addition to the current tensions between white and black, men and women, rich and poor, there are also other differences, such as those between Orangists and republicans. And of course there are also tensions between those who consider these as relevant questions and those who are not so interested in politically charged perspectives. The latter aspect particularly plays a role with regard to the Golden Coach. For some, it represents an aspect of our fraught heritage that should never be driven in public again, because it is the ultimate symbol of systematic racism in our society; for others, it is a beautifully crafted object that is part of the festive celebration of the bond between the Netherlands and the House of Orange.

The Amsterdam Museum’s ambition is to present an exhibition about the Golden Coach which does justice to all these different views and social tensions. That is why the exhibition is part of a research project with a focus on polyphony. We sought out well-known and lesser-known histories surrounding the coach, its use, and the current societal discussion about the significance and future of this controversial gift. In doing so, we operated from the conviction that by bringing different perspectives together, understanding and connections will emerge, even while these often seem to be lacking in today’s society.

Danielle Hoogendoorn, We are not cattle, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

By gathering an interdisciplinary research team, we were able to achieve these ambitions. Eleven curators, educators, researchers, programmers, and experts in the field of communication and marketing worked together on this multifaceted project, each from their own specific area of expertise, perspectives, and interests. In addition to historical research, which begins from current affairs and is aimed at focusing on perspectives which have not been thoroughly examined before, a public survey plays an important role. It is about listening to what is going on in society. What do people actually know about the coach? What memories do they have? And who lacks such memories, but is curious to know more? What do people think should be done with the coach in future? In order to gather answers, a research team with a mobile installation traveled through the country prior to and during the exhibition. In cooperation with local partners, the museum’s presence with a mini-exhibition in the twelve provincial capitals invited people to share their memories and perspectives of the Golden Coach.

Discussions with the public were also held in the museum itself, prior to the exhibition. More than six months before the exhibition opened, a Golden Coach Study Room was set up as a public research center. There, the research team worked on the project and invited visitors to contribute their thoughts. The room served as a meeting place, displayed information which was gathered in the provincial capitals, and gave behind-the-scenes insight into how the exhibition was being put together—a process normally not visible to the public.

Golden Coach Study Room in the Amsterdam Museum, 2020.

In order to adopt a critical and questioning attitude as exhibition makers, we set up a sounding board group of more than twenty experts: from academics in the field of Dutch history, like James Kennedy and Anne Petterson, to heritage experts like Susan Lammers and Vim Manuhutu; from experts in Dutch literature and (counter)culture like Marita Mathijsen and Geert Buelens, to pioneers in the field of heritage decolonization like Susan Legêne, Simone Zeefuik, and Jennifer Tosch; from specialists in the rituals and collections of the royal family, like Johan de Haan and Irene Stengs, to activists and campaigners for equal rights like Simon(e) van Saarloos. The sounding board group met every month to comment on and ask questions about the various plans. Are we on the right course? Are we missing important perspectives and voices? How can we best present the many different perspectives and storylines? The discussions we held were always lively, critical, and constructive.

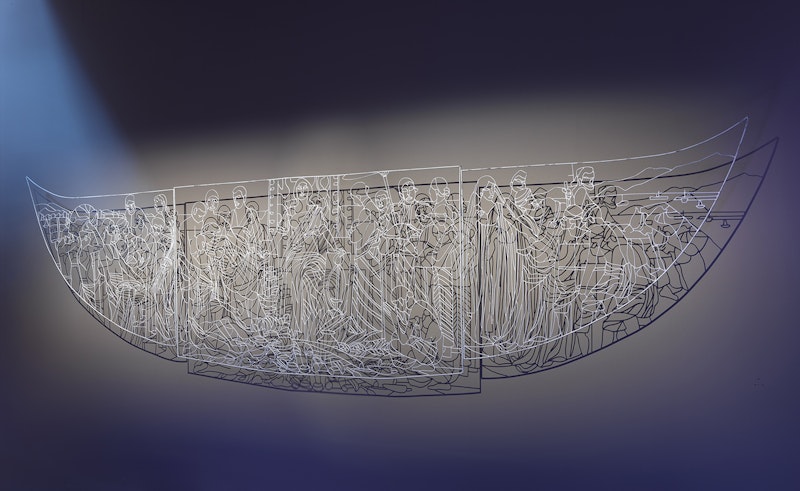

For a polyphonic view of the Golden Coach, a number of commissions were given to artists with diverse (bi)cultural backgrounds. Together with a selection of relevant existing work, these artists provided a range of new critical and artistic perspectives. The majority of the work is presented in the museum’s famous twelve-meter-high Amsterdam Gallery, which was completely emptied for this exhibition. In addition, some of the artworks are spread throughout the cultural and historical route through the museum, including Colonies by Iswanto Hartono, which has been in the museum’s collection since 2018. This is a large line drawing of the contours of the Tribute from the Colonies panel, executed in white steel wire. The crux of the work is that the wire sculpture is illuminated, producing a shadow of the drawing on the wall in black. Hartono subtly reveals in this way the tensions between white and black, the ruler and the ruled. Both literally and figuratively, it addresses the dark side of Dutch colonial power and its representation on the Golden Coach.

Iswanto Hartono, Colonies, 2017. Collectie Amsterdam Museum. Courtesy de kunstenaar.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, preparations for the exhibition did not go as planned. The preliminary discussions with artists and sound board group sessions took place digitally, while the planned circuit of the research installation through the country, as well as the research team’s work in the study room, turned out to be only partially possible prior to the exhibition, and were therefore continued during the exhibition. However, a start was made on a digital public program, both before and during the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021. Every two weeks on the museum’s online talk show, AM LIVE, attention was devoted to the preparations for the exhibition and all the related research (see www.goudenkoets.nl/en/public-program). Senior curator Annemarie de Wildt, for instance, took us back to the time when the coach was built, discussing why the court initially did not want the coach. In addition, fundamental discussions which took place in the sounding board group were further explored for the public, such as who actually has the final say over the coach. Pieter Verhoeve, president of the national umbrella organization for Orange Associations, is of the opinion that it belongs to King Willem-Alexander, and that he can therefore decide how the vehicle will be used. Hans Ulrich Jessurun d’Oliviera, a member of the Republican Society and a legal expert, stated that it is the Prime Minister who is ultimately responsible for everything the king says or does. AM LIVE also highlighted the troubled relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia, whereby Jeffry Pondaag kicked off a discussion between Lara Nuberg and Wim Manuhutu. We also considered the position of women at the end of the nineteenth century. Wilhelmina may have been the first woman to ascend the throne in the Netherlands in 1898, but women’s suffrage would take another two decades.

Senior curator Annemarie de Wildt, for instance, took us back to the time when the coach was built, discussing why the court initially did not want the coach. In addition, fundamental discussions which took place in the sounding board group were further explored for the public, such as who actually has the final say over the coach. Pieter Verhoeve, president of the national umbrella organization for Orange Associations, is of the opinion that it belongs to King Willem-Alexander, and that he can therefore decide how the vehicle will be used. Hans Ulrich Jessurun d’Oliviera, a member of the Republican Society and a legal expert, stated that it is the Prime Minister who is ultimately responsible for everything the king says or does. AM LIVE also highlighted the troubled relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia, whereby Jeffry Pondaag kicked off a discussion between Lara Nuberg and Wim Manuhutu. We also considered the position of women at the end of the nineteenth century. Wilhelmina may have been the first woman to ascend the throne in the Netherlands in 1898, but women’s suffrage would take another two decades.

Erwin Olaf, Entourage, 2021.1st Head Groom with Riding Horse. Courtesy of Ron Mandos Gallery, NL. With thanks to the Royal Stables

Decolonization and the future

In short, research into the Golden Coach in 2021 produces a range of different narratives and perspectives; a kaleidoscope, but clearly anchored in the here and now, a time when a fierce debate about fundamental inequalities and racism is going on in society. But the continued impact of the colonial past of the Netherlands and its involvement in slavery has only recently seriously been taken into consideration. For a long time the Netherlands saw itself as a guiding light when it comes to tolerance, but it is now clear that this is not the whole story. Acknowledging histories of oppression and exploitation goes hand-in-hand with a critical look at their impact on contemporary society. When this means that traditions must be changed, it is not without a struggle. It is only since 2020, for example, after more than nine years of activism—including violent intimidation by opponents—that a small majority of society will no longer accept Zwarte Piet (a character who is often portrayed by people in blackface and is the companion of Saint Nicholas) as part of the national children’s festivities known as Sinterklaas. In short, changes are taking place, but the Netherlands is by no means leading the way internationally. Museums can provide a valuable contribution to promoting social equality and opposing racism. We can create greater awareness about the colonial past by organizing exhibitions about related subjects. In addition, we can take a critical look at our collections; which objects from the past have been preserved, which stories can we tell with them—and which cannot be told? Critical reflection is needed regarding how we tell these stories. What words do we use? Perhaps these words already create invisible barriers, so that an inclusive and polyphonic presentation becomes impossible. As was powerfully formulated in the guide made by the National Museum of World Cultures that is widely used in the museum world: Words Matter.

In September 2019 the Amsterdam Museum decided to no longer use the term “Golden Age” as a synonym for the seventeenth century. For us, it was a decision which resulted from the New Narratives program, in which we invited a range of creators and critics to take a critical look at the way in which we presented our collections (which are full of seventeenth-century masterpieces). They made it clear to us that the term “Golden Age” does not do justice to the dark side of Dutch wealth during this period; it was certainly not a Golden Age for everyone. When our decision became known, a heated national discussion arose, dominated by disapproval and lack of understanding. Prime Minister Mark Rutte commented that he “was so tired of these sorts of discussions.” The Minister of Culture, Ingrid van Engelshoven, stated that “history cannot be rewritten.” While the aim was to provide space for layers of interpretation and polyphony, we were mainly reproached for contributing to polarization.

Nelson Carrilho, Altar for Elisabeth Moendi, 2017. Photo: Tom Benavente. Courtesy of the artist.

The fact that the king loaned us the Golden Coach a few months later was an important sign of encouragement. This trust in our serious task to create a meaningful exhibition about the gift to his great-grandmother inspired us. We worked with much enthusiasm on a cultural-historical narrative with many voices and artistic reflections. Together they show that we can talk about histories with controversial heritage and make them tangible, histories which inspire new images and new reflections about who we were, who we are, and who we will be.

When the exhibition concludes, at the beginning of 2022, the official owner of the Golden Coach will decide on the future of this heritage. The symbolic donors and co-owners of the coach—the people of the Netherlands—will also be able to do so by that time, through the exhibition, the accompanying programming, and this publication. We hope that this will reduce the distance between all those who feel involved. In this way we can demonstrate together that a controversial history, and the heritage that is a reminder of it, does not have to be divisive, but rather provides an excellent opportunity to cultivate mutual understanding and work together on a society which more than before is based on equality and connection.

This essay is a slightly briefer version of the introduction to the publication The Golden Coach (Zwolle: WBOOKS, 2021).